What can Descartes teach us about data? Professor Don Fallis explores the intersection of computer science and philosophy

Author: Madelaine Millar

Date: 10.22.21

To write good code, every variable needs to be well defined. To make the written code written do positive, impactful work in the wider world, everything else—from goals to the strategies used to achieve them—needs to be well defined too. At least that’s what Don Fallis, a professor of philosophy and computer science at the Khoury College of Computer Sciences, believes.

Professor Don Fallis.

Professor Don Fallis.

Taking an interdisciplinary, philosophical approach to the questions of deception posed by modern technology allows Fallis to grasp the wider landscape of the field and see connections he might miss working as a programmer or a software developer.

Why should computer science students study philosophy?

Although Fallis created the term adversarial epistemology himself, the concept is nothing new. People have been lying to and deceiving each other for thousands of years. Modern technology opens up new tools and techniques to make practicing deception easier, from deepfakes to fake news to AI. As such, it’s unsurprising that Fallis finds a lot of classical philosophy still relevant today, and he provides a foundation on it in his classes.

“I’m always finding quotes in David Hume and Descartes that I say, ‘Look, it sounds like he’s talking about Twitter there!” said Fallis.

Fallis’s primary course, “Knowledge in a Digital World,” is cross-listed in philosophy and computer science. Fallis believes the best epistemology is inherently goal-oriented, so he starts the class by trying to figure out exactly what students mean when they say they want to acquire knowledge.

“Does it mean I want to have a lot of true beliefs? Does it mean that I want to have very few false beliefs? Does it mean that I want my beliefs to be justified? Does it mean that I want a lot of people that have these things? Does it mean that I want to have these things very quickly?” explained Fallis. He elaborated that, while any of these goals would qualify as acquiring knowledge, the tools and methods used in each scenario look very different. “Getting clear on your goals is going to put you in a better position to decide what sorts of particular technologies and policies are going to be the best way to achieve those things.”

Once students have considered their epistemological goals, Fallis has his students each pick a specific technology—anything from a specific subreddit to the GPS app on their phone. They spend the course learning to evaluate its epistemic costs and benefits using a range of philosophical frameworks. He intends for students to leave the class understanding not just their own technology, but how to evaluate future technologies in order to engage with them more critically and avoid the deceptions they could create. Fallis believes that learning to think in this way is particularly useful for computer science students, who will someday be designing technologies of their own to help people acquire knowledge.

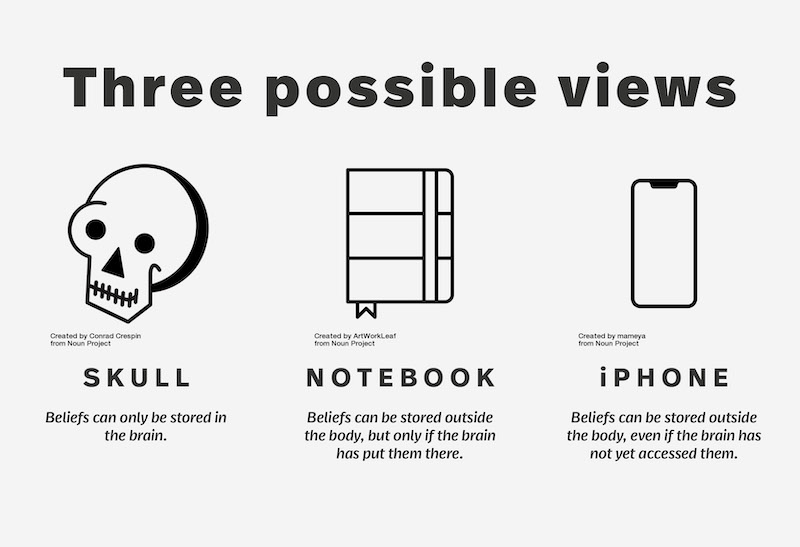

Information from Fallis depicting the three possible views on storing beliefs.

Information from Fallis depicting the three possible views on storing beliefs.

“Computer science students are basically in the business of what you might want to refer to as information intermediaries. They’re helping people acquire information, if they’re a technologist or a librarian or whatnot. If they’re a cybersecurity expert or a software developer of some other sort, then they’re developing the technology that various people in the world are using to communicate and share information,” explained Fallis.

He added, “Having this theoretical understanding of how people acquire knowledge, how technology can affect how people acquire knowledge—that can all be useful, especially if you’re interested in being an ethically enlightened information intermediary.”

Using philosophy to spot connections

Much of Professor Fallis’s research work is focused on finding or creating definitions. He’s written papers in the past attempting to define lying and disinformation; he’s now working on a taxonomy of the different kinds of deception that he hopes will be useful in the world of cybersecurity.

Fallis has found that taking the time to step back and create exact definitions and categories allows him to see powerful connections between different kinds of deception that he would have otherwise missed. He gave the example of a browser that automatically clicks on all the ads in the background of a page.

“Say you’re shopping for shoes—you click on the shoe [ad] and then, the next day, the next hour you start getting ads on your feed saying, ‘here’s some shoes you might like’,” said Fallis, describing an interaction that users are accustomed to. But such a browser adds a, well, sneakier interaction that is far less familiar to users. He continued: “What this browser does is it hides what you’re up to in this mass of information, so the person tracking you can’t tell that you’re [shopping for shoes].”

The second interaction is deliberately misleading, among a set of what he called “techniques for preventing somebody from acquiring a particular piece of knowledge that you don’t want them to acquire.” According to Fallis, it would be insufficient to approach this as a one-off example of deception. “That counts as what counterintelligence agents call Dazzling,” he explained, adding that “there’s these other ways you can Dazzle that you might not even have thought of, but they have the same structure so you should watch out for that.”

Once a user knows what a technique looks like, they’re empowered to recognize and combat it when it’s being used against them, and additionally equipped to imagine scenarios—like the browser—where it could be used to protect you instead.

Unlike many more traditional computer scientists, Fallis doesn’t have a straightforward checklist of how to stay safe online — change your passwords regularly, set up two-factor authentication, don’t click on suspicious links, and so on. (Although he does think those are all good ideas.) Instead, he believes that the best way to protect yourself is to understand your adversaries and what they can do.

“[My pitch is basically] if you study philosophy with me, you’ll have a better understanding of the world,” said Fallis, “and the better that understanding it is, the better position you’ll be in to deal with these different phenomena.”

Subscribe to the Khoury College newsletter

The Khoury Network: Be in the know

Subscribe now to our monthly newsletter for the latest stories and achievements of our students and faculty