Students in remote areas often leave to pursue AI. These researchers are helping them stay

Author: Attrayee Chakraborty and Milton Posner

Date: 08.16.24

For researchers focused on making AI education accessible to as many learners as possible, the word “remote” can denote either a challenge or a solution.

In remote communities, many residents fall under the broad umbrella of “nontraditional learners” — students who face economic or logistical barriers to education, especially in more specialized subjects like AI. But remote learning platforms, which have grown in capability and ubiquity since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, offer those same learners an opportunity for instruction and collaboration around AI.

In their recent paper, University of Victoria researcher Derek Jacoby, Khoury professor Saiph Savage, and Victoria–Khoury professor Yvonne Coady examined the experiences of remote AI learners and discussed ways of further incorporating AI education into remote work-integrated learning (WIL). In doing so, they hope to design AI-enhanced tools that will help rural students develop digital skills and access new online jobs so they won’t have to abandon their hometowns.

Critically, the team’s approach is community-driven, centering the Four Rs of Indigenous research and education: respect, relevance, reciprocity, and responsibility. Through participatory design, remote and hybrid work platforms, co-creation and collaboration tools, and collaboration with community makerspaces, public libraries, and nonprofits, the team is striving to create culturally sensitive educational experiences for communities that might otherwise miss out on AI education.

“The work began with meeting Saiph at the Vancouver campus,” Coady says. “We were contemplating if we could work together to understand how AI could be used in remote communities.”

Their project is powered by funding from the NSF and from Northeastern University, which offers grants to facilitate collaborations between network campuses — in this case, Vancouver and Boston. Coady’s dual association with the University of Victoria and Northeastern Vancouver also helped kickstart the collaboration.

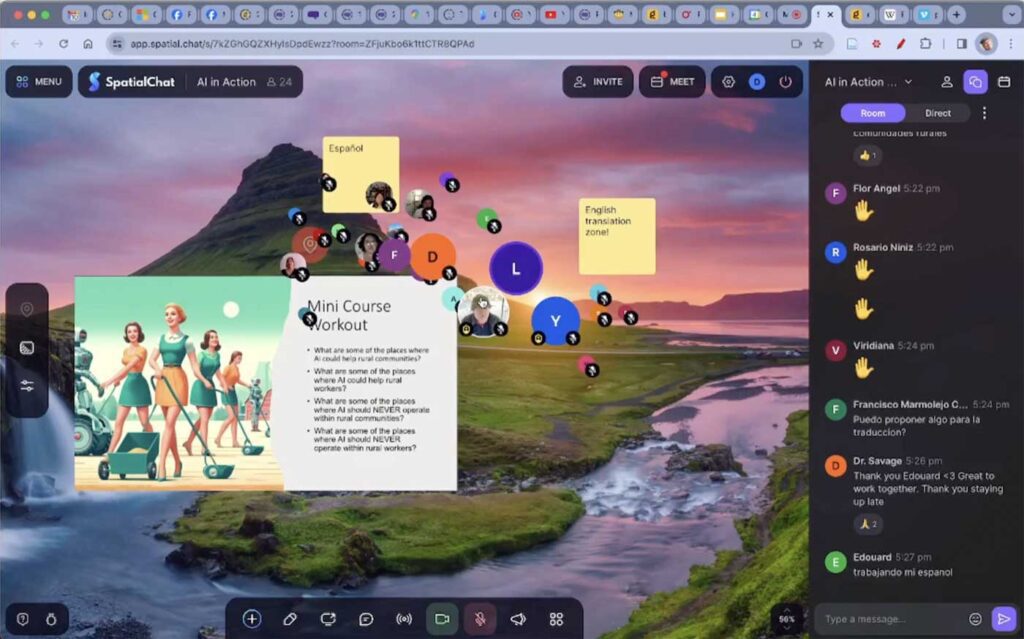

“We’re leveraging the global campus aspect of Northeastern to work with rural workers in the United States, Canada, and Mexico,” says Savage, who directs Northeastern’s Civic AI Lab. “We also promoted AI literacy among rural women through AI in Action Week at Northeastern, and Yvonne conducted workshops centered around AI-based solutions and natural resource management this Earth Day.”

The researchers began their work-integrated learning program by defining the skills learners would attain, then collaborating with public libraries to focus on practical computing skills that would translate well to local job markets. After the classes launched, the researchers adjusted their program based on participants’ feedback to ensure the curriculum was relevant and impactful for them.

“We must consider how material gets presented and consumed in a real collaborative format,” Coady says. “Instead of delivering a standard curriculum to these communities, we need to develop creative new ways of teaching that foster reciprocal learning.”

The researchers, understanding the shortcomings of previous technologies designed with rural communities in mind, instead elected to hold collaborative, participatory forums in which communities built infrastructure for themselves. Those forums, combined with the team’s attention to the design details of AI-enhanced tools, aimed to provide an economic boost to historically underserved regions.

“Usually people conduct studies, publish findings, and then arrange for ways to disseminate those findings,” Savage says. “We realized that we had to immediately give back to communities to engage them, which we did through workshops.”

In one such collaboration, the researchers worked with the Indigenous Matriarchs Four Lab, assisting remote Indigenous filmmakers in the use of sophisticated AI tools like motion capture models and generative AI for asset creation. Elsewhere, Northeastern graduate students extended the Spatial Chat platform and created speech-driven avatars for users with autism who often struggle to speak.

“This is another interesting aspect of how Northeastern operates,” Savage says. “Where we’re combining CS plus something else.”

READ: Matthew Goodwin showcases aggression-predicting autism research in APA keynote

Where possible, the team designed opportunities that leveraged ongoing initiatives and the educational infrastructure that the rural communities already had. Coady cites an existing project to bring high-speed internet to remote, rural, and Indigenous communities in British Columbia, while Savage notes the team’s connections with rural libraries, which ensure students’ access to computers and the internet.

The team also created a certificate on culturally aware AI through CIFAL, which is part of the United Nations Institute for Training and Research. So far, 44 Victoria students have earned the certificate, which Coady hopes will be offered as a Northeastern badge soon.

In the coming months, the researchers hope to expand the scope of their work and bring in participants from Vancouver, West Virginia, Victoria, Seattle, San Jose, and Mexico for future events.

“What we aim to do is visioneering beyond engineering,” Coady says. “There are opportunities to engage all learners in a way that has never been done before, where participants have a say in the creation of solutions that affect their lives. If we can get this going, this could be a real game-changer in developing culturally sensitive, accessible, and relevant solutions.”

The Khoury Network: Be in the know

Subscribe now to our monthly newsletter for the latest stories and achievements of our students and faculty