Proteins and pathogens: a behind-the-scenes look at a biomedical researcher’s best friend

Author: Madelaine Millar

Date: 02.23.24

Khoury College–College of Engineering researchers Ben Gyori (left) and Charlie Hoyt.

Khoury College–College of Engineering researchers Ben Gyori (left) and Charlie Hoyt.

If you went to a library at the turn of the 19th century to learn about proteins, good luck. The Dewey Decimal System did not exist yet, so books were shelved using an organizational scheme unique to each library. You could use an encyclopedia, but to dig deeper, you’d need to know how that specific library classified books about proteins. Not to mention, when a librarian departed, their institutional knowledge moved on with them.

Today, if you parse the roughly 35 million indexed biomedicine publications for information about a specific protein, you’ll run into a similar problem. While existing ontologies and databases compile and organize knowledge on specific topics, biomedicine has long lacked an equivalent to the Dewey Decimal System — a unified, open-data-compliant way to identify, organize, and network together information about billions of researched entities, from chemicals and proteins to phenotypes and diseases. That difficulty in locating what we already know slows down research and drug discovery, and it means that existing data goes underused.

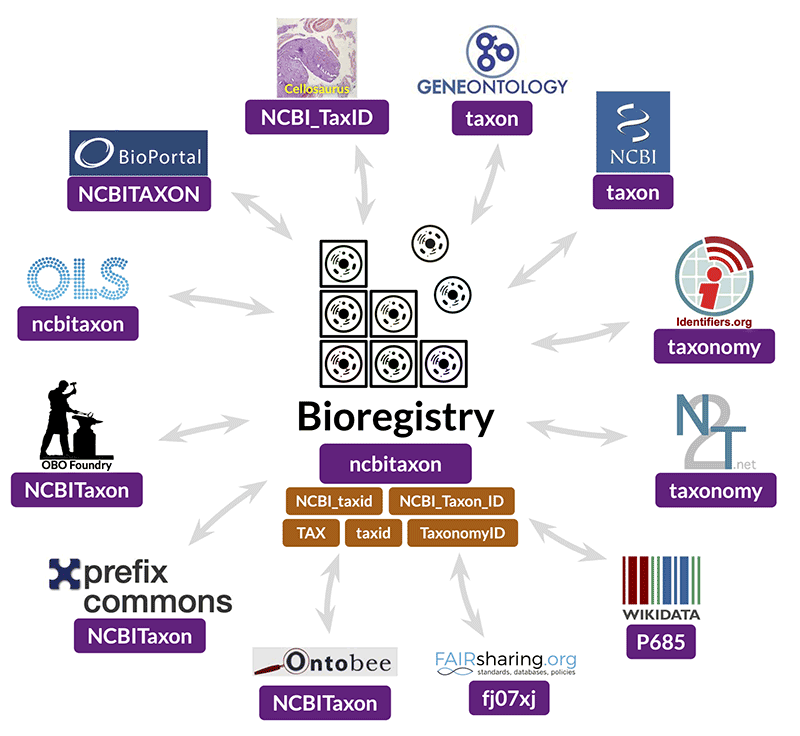

But Ben Gyori and Charlie Hoyt of Northeastern University’s Gyori Lab for Computational Biomedicine are working on a solution. The Bioregistry is a comprehensive resource that labels every biological entity — from proteins and molecules to diseases and pathogens — with unique, standardized identifiers that are linked together. Identifiers are crucial for data integration, but their use in the biomedical community is still limited and highly inconsistent.

The Bioregistry irons out these inconsistencies and allows researchers to more easily locate information in their areas of interest. And with two years of new funding from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, Gyori and Hoyt aim to expand the tool’s scope and integrate it more deeply into the scientific community.

“We need technologies that allow for different pieces of existing research to be put together in a consistent way,” explained Gyori, an associate professor jointly appointed between Khoury College and the College of Engineering. “This will accelerate the scientific discovery cycle by making it easier for researchers to leverage the body of knowledge that is out there.”

The Bioregistry had a humble beginning. While working on systems biology and network science projects, Hoyt kept encountering a persistent problem; the literature and the data were filled with entities referred to by identifiers that he couldn’t recognize.

“Many widely used databases we were integrating with our tools were using different synonyms and capitalizations and styles for providing identifiers, and it was often impossible to tell what they were; on occasion I even had to ask people by email,” said Hoyt, a senior scientist within Gyori’s lab. “Every time I got an answer, feeling like I was a digital Indiana Jones, I wrote it down. I wrote enough of these down that I realized this could be its own resource, and that it would be helpful for other people.”

At the time, Gyori, a recipient of DARPA’s Young Faculty Award for his work on accelerating biomedical discovery, was already working with Hoyt. He saw the potential of Hoyt’s idea to further not just the lab’s goals of large-scale integration of biological knowledge, but to improve biological research in general.

“If you’re on a mission to solve a specific problem, you often run into limitations you didn’t anticipate. If you then find a general solution to that problem, that will also help other people in the community,” Gyori said. “The Bioregistry is one example of that. We needed it to achieve our own ambitious goals, but we’re making sure that we not only solve this problem for ourselves, but create a resource that’s broadly useful for the community.”

Since then, Hoyt and Gyori have made significant progress. They have cataloged almost two thousand resources that provide identifiers for biological entities, making it easier to locate information about billions of individual biological entities. They have also built a semi-automated curation workflow to support community contribution to the Bioregistry, where researchers can add entries based on their own work.

The whole resource is compliant with the Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR) data principles and open science standards, which Gyori believes is critical to making the project widely available and sustainable.

Now, after three years of building the Bioregistry from an idea into a functional piece of technology, it’s time for a different flavor of work. While other projects have sought to solve a similar problem before, they have been limited by their institutional ownership and noncompliance with open data practices. With the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative’s support, Gyori and Hoyt will spend the next two years working to ensure long-term sustainability for the Bioregistry — building out a community-oriented governance model, expanding its scope, and pursuing integration with a broad set of other projects. It’s important to the duo that the Bioregistry’s usefulness outlasts their research tenures, and to do that, they need a community that will continue to use and update the resource independently.

“For externally funded research, it is our responsibility to make our work available openly and broadly. But beyond that, we are developing a blueprint for creating resources in a way that ensures sustainability if funding for the original developers runs out, if people change careers, or if anything happens,” Gyori said. ”With the Bioregistry, we not only made a larger and more comprehensive resource, but we came up with a framework that allows for further growth initiated by the community.”

While organizing scientific data integration might sound obscure, its potential influence is difficult to overstate.

“It has a big impact, even though it’s something people might not be aware that they’re relying on — the same way that roads are fundamental to a functioning society,” Hoyt said. ”Personally, I’m a neat freak. I see the world of fragmented biological data as a puzzle that needs to be solved. I think the Bioregistry is a key part of the solution.”

Subscribe to Khoury News

The Khoury Network: Be in the know

Subscribe now to our monthly newsletter for the latest stories and achievements of our students and faculty