This is Khoury College

Computer science for everyone

At Khoury College, we believe computer science is for everyone — transforming nearly every aspect of our daily lives throughout all industries. As leaders in CS education and research, we are driven to make a positive impact and are vigilant about the responsibility that entails. It’s only by seeking curious thinkers with diverse backgrounds and perspectives that we can maximize the power of computing for the benefit of all.

Practical education, real-world preparation

We’re known for flexible, innovative programs designed to help every student reach their unique goals — through industry co-ops, interdisciplinary programs, and research opportunities.

Research for impact

Every day, our leading researchers and talented students collaborate in world-class facilities to make new discoveries and create equitable opportunities across industry and society.

Programs on nine of Northeastern's global campuses

Locations in technology hubs around the world, including Northeastern’s main campus in the heart of Boston, give our students and faculty access to study and work across a global network — living and learning where the action is.

A culture of belonging

We embrace and empower curious problem-solvers from varied backgrounds — because multiple perspectives lead to the innovative solutions we need for society’s biggest challenges.

Supportive, creative people

Our world-class faculty, leading researchers, experienced staff, and talented students are the heart of Khoury College. Together, they are preparing the problem-solvers of today and the thought leaders of tomorrow to tackle the challenges of our times.

Leading industry partners

We partner with more than 800 industry and community leaders around the world — empowering our students and faculty to make meaningful contributions, solve complex problems, and learn through hands-on experience.

Khoury Statistics

60 combined undergraduate majors: Dream big and pursue your passion

Passionate about philosophy but have a knack for computer science? Looking for a career in data science anchored in a firm understanding of business administration? Northeastern University’s combined majors — unique, hybrid degree programs — offer unprecedented opportunities to chart your own educational journey.

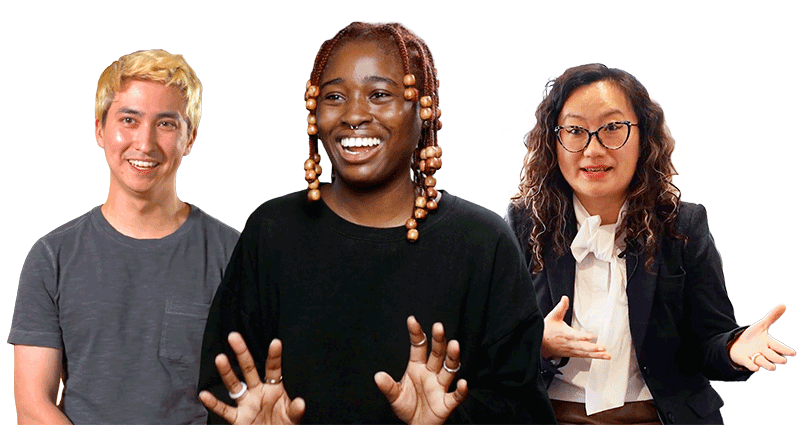

My Khoury Story

Meet the students, faculty, alumni, and partners who are pushing boundaries, solving real-world problems, charting their own unexpected courses — and living out our mission of CS for everyone. From first co-ops to groundbreaking research, this is Khoury College — and these are our stories.