Inside the First Season of Northeastern’s Varsity League of Legends Team

Author: Milton Posner

Date: 01.25.21

Image credit: Upsurge Esports

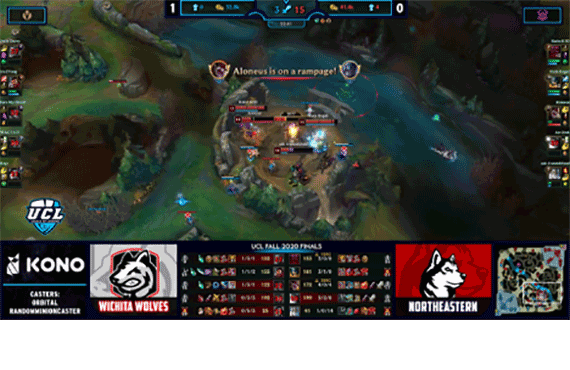

In the early hours of December 11, after a brutal and dramatic fight, Northeastern’s League of Legends team finally succumbed to the Wichita Wolves in the championship match of the Upsurge Contenders League.

Their two-and-a-half-month tournament run, spearheaded by eight wins in 11 matches, came as the team made a strong run in a concurrent tournament: the College League of Legends Fall Invitational. While both stand as commendable achievements in and of themselves, they are all the more striking considering that the team, like Northeastern’s other three esports teams, wasn’t even a varsity squad eight months ago.

“[Our] losses showed us that we could scrape with these schools with big names,” varsity coach Christopher Bravo said. “There are already schools that have names in the same way that in football there are schools that have names. At this point, I would argue Northeastern does not yet have a name. That’s what we’re out here to do.”

The rapid growth and success of the League of Legends squad is a testament to the drive of the players, the adaptability of their coach, and a healthy dose of Khoury College firepower.

The Season That Was

League of Legends is a strategy game contested between two teams of five players. Each person picks a character (called a champion) and aims to attack the enemy’s base while defending their own. To win, a team must work its way through a series of enemy turrets before destroying the Nexusat the back of the opponent’s base. This can be done using the champions as well as minions, which spawn in each of three lanes and advance toward the enemy.

Fourth-year Khoury College student Ryan Folz plays the support position on the team’s “starting five,” so his responsibilities are more flexible and creative than, say, a player who mostly attacks and defends within a single lane.

“I have a lot of time to think and move around the map,” he says. “So it’s easier for me to think about what we do . . . I’m usually the one who is leading the way.”

Coach Bravo (left) meets with League of Legends player in photo (2020) by Tyler Levesque/NU.

But he says positional versatility has been a hallmark of the team’s growth in the first half of its first season as a varsity program. For instance, when third-year biology student Toby Kaufman took over for Folz as the team’s jungler — who kills neutral monsters in the jungle between lanes to maximize resource accrual and allocation — he brought a welcome new approach.

“He does a much better job of acting in an independent carry role, so I don’t really have the pressure to act as a carry anymore,” Folz says. “With that swap, the consistency and having someone else take over the jungler role, it’s been really helpful. I feel like I can rely on my teammates a lot more this semester than I could last year.”

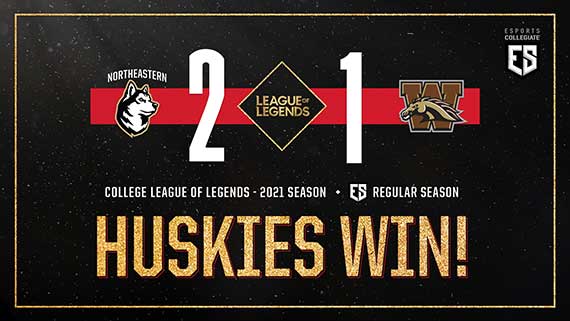

Folz says the team’s success this season — 13 wins in 18 matches — is largely a function of improved consistency, that players can better recognize when they’re struggling and take steps to rebound.

“They know how to push when we’re ahead,” he remarks. “A lot of the cracks in our synergy have been filled pretty well. Most of scrimmages we’ve had recently have been against really good teams, and we’ll stop early because [the opponents] just aren’t good enough.”

He paused for a moment, then added, “We don’t tell them that, of course.”

What It Means to Coach Esports

Christopher Bravo began his Northeastern League of Legends journey several years ago, playing on the club team at a time when club was the highest level. Even after he graduated Khoury College in December 2019 and found a full-time job that excited him, he couldn’t bear to sever his ties.

“My way of giving back was transitioning to a coaching role so I could still be involved and help my community,” he remembers. “When it was a club sports position, it was fully volunteer. There was no feasible way to finance living; I would have to be doing my full-time software job. I was prepared to do it that way; I was really enjoying it. But once I found out it was going varsity, I started thinking in the back of my mind, ‘Do I really enjoy software?’”

The answer, it turned out, was “yes,” just not enough to keep him from the coaching responsibilities he loved. After six months in software, he went all in on esports, becoming the first varsity head coach for Northeastern League of Legends. And he brought his computer science background with him.

“I learned a lot of technical stuff in my time at Khoury, but I took it as a way to think about the world,” he explains. “One big part of my coaching process is directly derived from the software development class taught by Matthias Felleisen.”

Bravo points to a concept called “egoless programming” or “egoless code review” that influenced him profoundly. Coined by computer scientist Gerald Weinberg in his book The Psychology of Computer Programming, it posits that productive, collaborative code review must be dispassionate and that the code be separated from the coder. Only then can inevitable mistakes be identified and rectified. Knowledge and improvement are the goals, not pride or ego.

“I wanted to bring that to sports from the world of software development,” Bravo says. “You’ve got to come together, look at the film, analyze together, and think about how to improve as a team. It’s a really nice way for us to move forward and a really good way to keep the space safe for learning, being critical of the game that we’re playing and what we’re trying to accomplish, and not being directly critical of each other as people.”

Bravo acknowledges that it might seem odd to apply code-review principles to a video game, but points out that “esports is oftentimes comprised of people who are in STEM. It’s natural. In a way, I feel like I’m imparting another skill to my players. You might go out and be programmers and do this as part of your job. I know I did.”

Folz, who just wrapped up Felleisen’s course himself, concurs.

“College in general opens you up to the fact that you could be wrong about a lot more than you think you are wrong about,” he says. “When you finish something and you show someone your work — or in this case, your performance — don’t hold onto it. Just let it go, move on, and be better the next time.”

Bravo acknowledges that, even with a background informed by his computer science education and gaming experience, he’s new enough in his esports role that he hasn’t quite solved his approach yet.

“Coaching is such a wild thing in esports because everyone has a different take on what coaches should be responsible for,” he observes. “How you divide up responsibilities hasn’t exactly been shaken down yet.”

Whatever his style, it seems to be working.

The Season to Come

Both Folz and Bravo cited the two large fall tournaments as akin to a preseason—preparation for a spring season that includes the tournament officially endorsed by Riot Games, the company that developed the game.

“If we win the Riot Games-sponsored tournament, that could mean a lot of openings into professional teams and more recognition for Northeastern,” Folz notes. “I’d like to see us go as far as we can in that bracket. We made it pretty far last year, but I think we have a stronger team now with people more comfortable with their roles.”

Image provided by Tyler Levesque/NU.

It will be Folz’s last semester, as he is graduating in May and will begin a site reliability engineering job with Google in New York City soon after. For his part, Bravo is weighing the future of team composition as the program heads into its second calendar year. While there is certainly value in recruiting top players with large scholarships — Northeastern does give a partial scholarship to all esports athletes — Bravo says he doesn’t want to ignore the school’s existing esports community, the one that gave rise to the varsity teams in the first place and the one that’s still going strong.

“The totality of the program that I’ve been trying to orchestrate is that we all learn the same ideas,” he explains. “I’ve been trying to extend that as far down the pipeline into the foundation as possible. I would like to create a talent pipeline where you can come in barely knowing how to play the game and walk out as a scholarship player.”

And Bravo thinks that pipeline, fortified in good part by Khoury students, can help to establish the Huskies as a national power as they prepare for the big spring tournament.

“At this stage of collegiate esports, it’s an anyone-can-win scenario,” he says. “We’re contenders with these schools that are developing and recruiting and doing all these crazy things. And we keep up. I think, in time, not only will we keep up, I would like to believe that we can actually crush some of that competition.”

For a longtime player like Folz, that sort of competition is what keeps things interesting.

“When you’re the one person left on defense standing between you losing or winning the game and you pull it off, it’s a really high high,” he says. “If I just played alone it would get kind of boring and repetitive. But playing competitively really gives me the drive to keep playing.”

The team’s matches can be viewed for free on Twitch.