How three Khoury College co-ops helped to rebuild an MLB team

Author: Sarah Olender and Milton Posner

Date: 04.06.22

A day at the stereotypical software engineering job starts with going into the office, or maybe logging on from home, grabbing a cup of coffee, and sitting down in front of a screen. Most don’t include a prime view of one of the most beautiful parks in Major League Baseball (MLB).

But that’s exactly where the Baltimore Orioles have their Baseball Systems Development co-ops working—right in Camden Yards, where Khoury College of Computer Sciences students Payton McAlice, Justin Chen, and Cam Gleichauf spent their last few months.

“It was a great environment to work at a ballpark every day and apply my love for math and statistics and computer science towards a goal that means something to me,” Gleichauf said. “It’s hard to beat that.”

While the Orioles posted a losing record in 2021, the co-ops were integral to an analytics team that worked tirelessly to improve that record in the future. Together, they helped to develop and revolutionize technology that leverages player statistics and data to improve the team’s potential.

The three had different journeys to Camden Yards. Chen, a third-year data science and business major, grew up in the Bay Area watching the perennially competitive San Francisco Giants. Even after he moved to Taiwan in fifth grade, he kept up with baseball, which has a large following there. His mother began throwing analytics books his way, reasoning that it made sense to connect his obsession to his school learning. By the spring of his first year at Northeastern, he’d begun working as a student manager for Northeastern’s baseball team—tracking pitching and batting metrics in Rapsodo, tracking college baseball stats with Synergy, crafting scouting reports, and charting scrimmages.

McAlice, a third-year data science student, got into the game because his father loved it. He grew up playing fantasy baseball and video game baseball simulators, which immersed him in analytics and allowed him to scout players from all teams. As McAlice got to know players and became fascinated by their statistics, his high school math courses revealed a potential academic and professional future in the field. Northeastern’s proximity to the Boston Red Sox was a big motivator in his choice of college.

Gleichauf, a fourth-year math and computer science major, fell in love with the sport while playing in youth leagues, and knew by middle school that he wanted a career in sports analytics. His favorite movie is Moneyball, which tells the true story of Oakland As general manager Billy Beane. Faced with a small-market financial disadvantage, Beane put his trust in analytics to more accurately evaluate players.

Beane’s success and the analytics revolution that followed made it possible, more than two decades later, for Gleichauf, Chen, and McAlice to work at the same task.

“The co-op was a perfect storm of everything I came to Northeastern to figure out and do,” McAlice said. “I lucked out getting into the position and fulfilling that part of what I’d wanted to do since I was a little kid.”

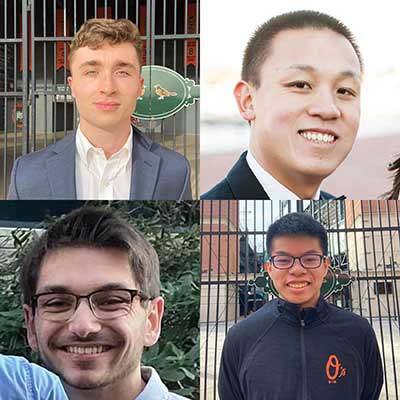

Image (clockwise from top left): Cam Gleichauf (co-op), Di Zou (supervisor), Justin Chen (co-op), and Payton McAlice (co-op).

Image (clockwise from top left): Cam Gleichauf (co-op), Di Zou (supervisor), Justin Chen (co-op), and Payton McAlice (co-op).

As the trio grew up and fell in love with baseball analytics, the “Moneyball” ethos was taking massive strides. Technology improved to track the motion of pitches, batted balls, and the players themselves. What began as a way for forward-thinking teams to gain an edge is now a universal part of baseball, and teams commonly boast ten or more full-time analytics professionals.

“To not have these tools would be penny wise and pound foolish,” Gleichauf said. “Every team makes day-to-day decisions that affect roster construction, who you’re playing, and where to play them. If you don’t have all the context, you’re making suboptimal decisions, and that’s going to hurt you in the long run.”

McAlice agreed, adding, “If you don’t have an internal website or app to help you develop your players, you’re shooting yourself in the foot for no reason.”

For a while, the Orioles fell into that category. When General Manager Mike Elias and Assistant GM for Analytics Sig Mejdal arrived from the Houston Astros in late 2018, they inherited one of the smallest analytics teams in the sport. The only developer on the three-person team was Di Zou, a lifelong Orioles fan who had joined the team in 2017 after working a sequence of software engineering and programming jobs in Maryland and New England. But Mejdal was credited for the analytics-driven approach that helped the Astros build their talent pipeline and win the 2017 World Series, and the two newcomers got to work.

“Mike and Sig came in, and the organization put more emphasis on analytics. We could grow the team a lot more,” Zou said. “So we started hiring, and that’s when the co-ops started too.”

The team began with one co-op in the spring of 2019 and steadily added a second and third position. Zou, the co-ops’ supervisor, notes that the team was happy with the quality of their work, and that the six-month timeframe allows enough time to onboard, ramp up, and still have time for longer, interesting projects. The goal was for each co-op to touch on every part of the team’s analytics work, which would let them determine which parts of software engineering they liked.

“You were free to jump around and pick up whatever project you wanted,” Chen said. “I think that was the best part.”

As it shook out, Gleichauf focused on the team’s internal mobile app, while Chen and McAlice worked plenty with their internal website.

“All our efforts go into presenting data in a way that makes sense, that can help the front office and coaches look at players more efficiently,” Gleichauf noted. Chen added that while each MLB team collects roughly the same amount of data, some teams are better with it, and this advantage lies in the ability of analytics personnel to make the data presentable.

They accomplished this, McAlice and Gleichauf explained, by accumulating, cleaning, managing, and analyzing game and player data from the team’s database, then presenting the data in the ways that scouts and coaches preferred. They also fixed bugs, spoke to scouts and coaches about which new tools they wanted, then created those tools for the app and website.

“The end users of the internal site or mobile app are people within the team,” Chen said, contrasting himself with a typical software developer serving a larger, more broadly defined user base. “You can consult directly with your consumers.”

“It was a really cool experience to talk to a scout and see where their head is at,” McAlice added. “Instead of a user base of a few million people, it’s the [hundred or so] people you message in Slack or see in the office.”

It also allowed them to expand their programming capabilities. For Chen, who spent a year as a business student before switching majors and diving into Khoury College’s Java-heavy early curriculum, it was largely about familiarizing himself with Python syntax and frameworks as he went. But he also worked with SQL tables and third-party data, built pipelines into the site, and rounded out the co-op with a full-stack project that yielded multiple tools for the team’s scouts.

“For every new project I was given, I learned something new,” McAlice said, noting his progress in web development, JavaScript, Python, APIs, and other data techniques. “It was definitely a challenge, but also very rewarding. I’m a lot more well-rounded than I was heading into it.”

Amid these learning curves, all three co-ops reported that team employees supported them and readily answered their questions.

“The people in the office are really good guys,” Gleichauf said. “Mostly a bunch of dads who like baseball, so it’s a pretty good vibe.”

That office, located on the top floor of the right-field warehouse at Camden Yards, was home for Chen and Gleichauf as they worked and roomed together in Baltimore for the co-op’s last four months. McAlice mostly worked from Massachusetts and said that even though it sometimes made it trickier to figure out tasks, the help he received from his co-workers made it as good an experience as a remote co-op can be. By the time he visited the office—and crashed with the other two—for a week in December, he had an optimistic outlook for the team’s future.

“The Orioles analytics department is relatively new and growing, and I think its progress will get the team closer to being competitive again,” McAlice noted. “I think we will see tangible results from the analytics team in the next few seasons. I think we’ll see a lot of developments from a lot of players.”

Gleichauf agreed, adding, “It was really cool seeing the end product and interfacing with coaches, analysts, the general manager, the front office.”

With their new knowledge and experience, the three don’t know for sure if this will be their future career, but they left the co-op excited about the experience and open to doing similar analytics jobs in the future.

“If you’re getting a degree in computer science or stats and you want to work in sports, a co-op is good for seeing if you really want it,” Zou said.

“It’s a dream come true,” Gleichauf reflected. “It’s the coolest job you could ask for.”

Subscribe to the Khoury College newsletter

The Khoury Network: Be in the know

Subscribe now to our monthly newsletter for the latest stories and achievements of our students and faculty