Epilepsy can make routine internet use life-threatening. Three Khoury researchers want to change that

Author: Milton Posner

Date: 07.12.21

Whatever your worst experience with social media has been, you can take solace in knowing that it was not as bad as Kurt Eichenwald’s.

In late 2016, Eichenwald opened a Twitter message that contained a strobing image along with text reading “you deserve a seizure for your post.” The Newsweek journalist, who had written publicly about his epilepsy, suffered a severe seizure. His wife found him on the floor.

A few months later, Laura South, a computer science and statistics undergraduate at Colorado State University at the time, read about the attack.

“This was the most publicly dramatic example,” she explains, “but it wasn’t the first instance of the problem by any means. It had been happening to people on the internet for a long time.”

South was in the market for an undergraduate thesis, and the topic aligned with her interest in computer vision. So she tackled as much of the puzzle as she could. And when she joined the Khoury College of Computer Sciences as a doctoral student in 2018, she wanted to take things further.

Armed with a three-year National Science Foundation (NSF) fellowship award for promising graduate students, and with her advisor Dr. Michelle Borkin and fellow doctoral student David Saffo on board, South did just that. Their groundbreaking paper — “Detecting and Defending Against Seizure-Inducing GIFs in Social Media” — was accompanied by PhotosensitivityPal, an open-source, first-of-its-kind browser plugin that South designed to help photosensitive users safely browse social media.

“This is about how we make the internet a more friendly, accessible place for people with photosensitive disorders,” Borkin says. “These are conditions that can’t be ignored.”

The idea comes together

Of the 65 million people worldwide with epilepsy, between 2 and 14 percent suffer from photosensitive epilepsy (PSE). For them, specific visual stimuli — flashes, repeating patterns, and transitions to and from saturated red — can trigger life-threatening seizures, as well as less serious seizures, migraines, and other symptoms.

This is why GIFs, particularly in volume on social media, pose a problem.

“If you’re browsing, scrolling through Instagram, looking at Facebook,” Borkin says, “you never think a scenario so mindless could be so dangerous for people.”

It’s part of why the issue goes unnoticed, including by researchers. That is, until South came along.

“When she was applying to doctorate programs, she talked to me about this research idea, and I was very impressed,” Borkin recalls. “I hadn’t thought about this. In fact, the entire data visualization community and a lot of human-computer interaction has not thought about this or addressed this. I was thrilled Laura chose to come be my student at Northeastern.”

In recognizing the idea’s promise at the nexus of vision science, computer science, and health science, Borkin also noted its implications for her primary field of data visualization, where numerous physical disabilities — including PSE, blindness, and colorblindness — can be barriers.

“This is the kind of research that could only happen at a place like Northeastern and in Khoury College,” she said. “We’re supported to do cross-discipline research and look for new fields of study.”

With Borkin supporting her, South applied for and received an NSF grant in 2019 to continue her undergraduate research. Only about 16 percent of applicants receive the grant, which covers tuition and salary for three years.

READ: Khoury Ph.D. Candidate Wins Prestigious NSF Fellowship

South knew that the browser plugin she’d proposed in her undergraduate thesis would be vital, since the research required a tool that could rapidly analyze many GIFs. But she also knew that such software wouldn’t qualify as research on its own. In came Saffo.

“I was set on making the software and doing the computer vision stuff; I have a background in that and I’m very comfortable with it,” South explains. “David was really helpful in planning and thinking through the best, most scientific way of running all of the additional components that are required to make it a research contribution.”

It was a good thing too. They had their work cut out for them.

The research and the accolades

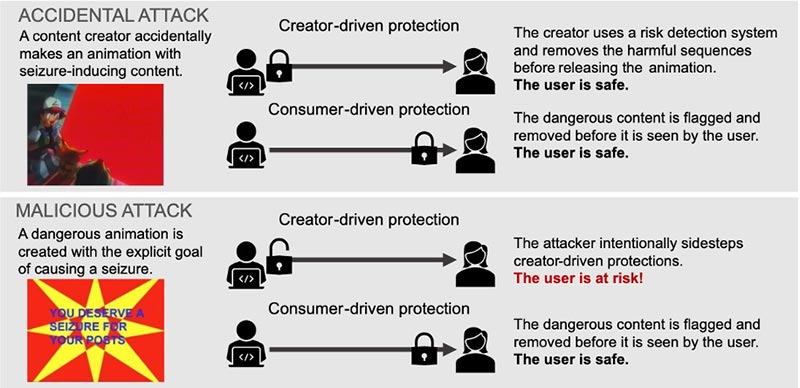

South, Saffo, and Borkin began their research with little to build on. Despite numerous attacks against photosensitive internet users, researchers had paid little attention to the issue. Much of the existing risk-detection software was aimed at content creators.

The trio also realized that the only existing consumer-driven system fell short, so they designed PhotosensitivityPal, then tested its effectiveness against existing creator- and consumer-driven systems. They decided it should actively check all animations and videos a user encounters, block items until it deems them safe, and allow users to view visually mitigated versions of blocked content if they choose.

“There’s been lots of discussion in accessibility literature about preserving independence for people who have disabilities, not just removing everything,” South notes. “They should still have some control over their experience. It shouldn’t be me, some researcher who doesn’t fully ever know their experience, deciding what they see and don’t see.”

PhotosensitivityPal equaled or outperformed existing detection tools in the three GIF datasets the team compiled, and is now available as a Google Chrome browser extension. South presented the trio’s work virtually at CHI (Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems) — the premier venue for human-computer interaction research — which recognized it with an Honorable Mention award designation that up to five percent of submissions receive.

It was another notch on South and Borkin’s academic belts. The pair won an Honorable Mention Poster Research Award at last year’s IEEE VIS — the premier conference for visualization-related work — with their poster: “Generating Seizure-Inducing Sequences with Interactive Visualizations.”

Nor is the CHI honor Borkin’s first. Last year, she received a Best Paper Award — given to just one percent of submissions — for research she worked on with, among others, her doctoral student Uzma Haque Syeda.

READ: Novel Framework for Implementing Design Studies Wins Best Paper at CHI 2020

Not that winning has gotten old for her.

“CHI is the most prestigious venue in computer science for human-computer interaction,” Borkin says. “It’s a real honor to receive this kind of award in recognition of our cutting-edge and highly impactful research.”

The future of photosensitivity online

Four years ago, Laura South became aware of a problem, one that has defined her academic career since. And with an estimated year and a half to go in her Ph.D. journey, she’s not done working on it.

As the PhotosensitivityPal website states, despite extensive testing and proven success, “the extension is still in beta and may not detect all possible forms of seizure-inducing content.” South and Borkin want to improve it. Borkin says they’re hoping to expand its reach beyond GIFs and videos to include maps, data visualizations, and other elements, while South wants to improve existing features.

“We currently use a rule-based approach [because it’s] really good at detecting flashes and red transitions,” she explains. “But it’s a lot harder to do a rule-based approach for patterns. So we’re interested in using machine learning to detect these patterns, and hopefully, a future version of PhotosensitivityPal will improve detection of patterns.”

But the solutions don’t end with the plugin. Borkin says that average users should think twice before posting risky material, with South adding that an epilepsy warning on such content is “a very low-tech, crowdsourced way of protecting people.”

But they both agree that more effective solutions lie in pressuring large social media companies to act, since platform-driven solutions work whether or not users act. In particular, the paper cites the practice of videos autoplaying on social media sites, which boosts engagement but poses a danger to photosensitive users. Some sites allow users to turn off this feature, others do not.

“They’ve been making strides,” Borkin said of Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and similar platforms. “Even since we’ve published the paper, more features have come out in a lot of these systems. If they implement more features to protect users, that would make it a lot easier.”

However, progress for photosensitive users, as with a number of lesser-known disabilities that impede internet use, can come only with wider public awareness.

“Sometimes when I tell people about my research and what happens, they’re … taken aback that it’s even a problem,” South says. “People want to believe that people on the internet are being nice and taking care of each other, but that’s not always true. It’s a real problem, and we all have a role in making the internet safer for other people.”

The Khoury Network: Be in the know

Subscribe now to our monthly newsletter for the latest stories and achievements of our students and faculty