Beyond the Desk: Q&A with Khoury advisor Ashley Armand on her new book, Marabou

Author: Jane Kokernak

Date: 05.05.21

Passionate about people and artistic endeavors, Ashley Armand is a graduate advisor for our Align program. Khoury News sat down with Armand to discuss her recent publication, Marabou, a book filled with lyrical poems and figurative paintings that guide readers on a journey filled with Caribbean culture, identity, and emotion. In the interview, Armand describes childhood trips to Haiti, lessons learned from her mother, the “privilege and honor” of her work with students, and her excitement about her book’s reception so far.

We’re here to talk about your wonderful book, Marabou. What can you tell us about the roots of this collection of poetry, prose, and paintings?

I have really enjoyed writing and creating and painting from a young age. I was raised by my mom, who is a mental health professional who centers her work in art therapy. She studied fine arts in her undergraduate career prior to focusing on mental health and vocational rehabilitation counseling. She loves art, and loves integrating art in every aspect of our lives. Growing up, my mother constantly fostered my ability to express myself. I love the power of language and linguistic diversity and expression, and I’ve mainly learned its true value through my mom, who also happens to be deaf.

About the connection between her artistic and academic sides, Armand says, “I love supporting and building relationships and networks, but also amplifying many different types of experiences and voices… That also relates to my artistic side because I’m able to create and develop new programs.” Photo provided by Ashley Armand.

About the connection between her artistic and academic sides, Armand says, “I love supporting and building relationships and networks, but also amplifying many different types of experiences and voices… That also relates to my artistic side because I’m able to create and develop new programs.” Photo provided by Ashley Armand.

As a CODA (child of deaf adult), I learned the value of language, human connection, and building relationships with people, but also what it means to tell a story with color and vibrancy, when others can’t hear it, but they can feel it. I ask myself, “What are some ways that I can express myself or tell a story in a way that amplifies so many different perspectives and voices and walks of life, but also develops a character in a way that still brings life?”

How did this collection of words and paintings develop into a book?

Marabou developed in a lot of different ways. As a child, I would often go to Haiti to visit my family. Whenever I’m in Haiti, I’m in a different state of mind. I think it’s because of how much of a paradise it is and simply how beautiful it is. It’s an amazing place to learn more about my identity.

While I’ve always been writing, I have never thought to publish myself. I thought because I didn’t study creative writing that I shouldn’t be able to publish something. I thought to myself, well, my mom emigrated here from Haiti, and I should be a lawyer or doctor. But the more I thought about it, I told myself, “I have all these poems here, what should I do with them?” I think when you write something, you’re supposed to let it go. So once you put your work out there, it carries, and other people read it.

Marabou is a strong hybrid collection, and the words and images are equally important. What are your thoughts on the different parts of your artistic identity?

For some time, I didn’t want to identify with my artistic identity in general, because I thought that wasn’t professional or a lucrative career. A lot of self-limiting beliefs do come from different aspects of our identity. Being Caribbean, and having immigrant parents, you’re taught that you can’t study art because it’s not lucrative. Haitian culture is really strict on school, church, and home. So, I think I’ve always had some sort of negative connotation with my artistic abilities. Yet, I had a mom who was an art therapist who said, “Okay, you should do this on the side.” Well, I’m already doing this on the side, I thought, but maybe I should put it out there that I’m doing this on the side.

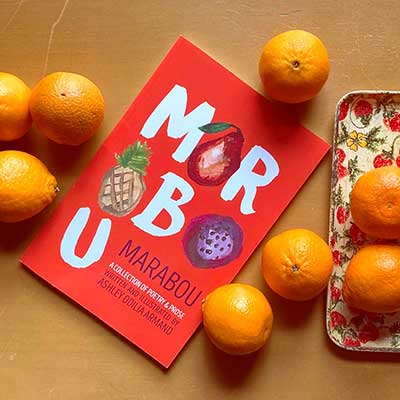

Marabou, by Ashley Odilia Armand (2020), is a collection of the artist’s poems, prose, and paintings. Image provided by the author.

Marabou, by Ashley Odilia Armand (2020), is a collection of the artist’s poems, prose, and paintings. Image provided by the author.

I started off with my paintings because I thought they were safer in a lot of different ways–also because I’m still learning how to be a great painter. I learned through really amazing mentorship that “great” is relative, art is art, and art is relative and subjective. That really inspired me look into more types of painting. In college, I did a lot of different poetry shows. Yet, to put my poetry out independently and self-publish was a huge deal for me. Now, I am an author, I am a poet, I’m a writer, I’m an artist, this is it. There’s no saying that “I’m not this,” there’s no saying that “I can’t do this and be a professional” because I can, and I have. I’ve learned to champion the fact that we can be multi-dimensional human beings.

Let’s talk a little bit about Khoury College, where you are an administrator and advisor in the graduate program. How do your academic and artistic sides express themselves at work?

I love advocacy. I love supporting and building relationships and networks, but also amplifying many different types of experiences and voices. I try to do that with programming. That also relates to my artistic side, because I’m able to create and develop new programs on topics that I’m interested in–that students are also interested in–and create them in a way that brings color and vibrancy to the student experience, much like I do with my paintings, and poetry.

Can you shift from talking about your overall mission to the way you relate to students?

It is a privilege to not only be able to support students, and advise them throughout their graduate program, but also be someone that students can lean on and trust. Students come to me with all types of concerns, academic, personal, or professional. I really enjoy that, and love being a resource.

I see my role and relationship with students as one that is encouraging, nurturing, and straightforward. I don’t feel like there should be a structure that makes people more anxious and more intimidated than they should be, and sometimes more scared to actually reach out to you. I aim to make advising as organic as possible, eliminating all structural and bureaucratic components (unless it’s needed for administrative purposes). I’d like for students to feel open and comfortable talking to me and feel supported in the process.

We’re excited about this opportunity to talk to you about your book Marabou and widen its audience. How have things been going so far with audiences and readers for your work?

The amount of support and love I’ve been receiving for the book is truly amazing. My high school purchased my book for students to read, and I was featured in the BlackTechPipeline as one of the must-have books by a Black woman this year. I’m so honored. I was featured in L’union Suite, a widely known Haitian American platform, headlined: “Marabou turns Ashley Odilia Armand’s voice into a literary symphony.” I’m also going to be featured in my undergraduate university’s upcoming magazine, and I’m really excited that it’s going to be featured in a magazine too.

For all of you who are reading, sometimes your biggest obstacle is yourself. At times, you have to ignore the self-limiting beliefs that you think of yourself, and just put yourself out there. Kick imposter syndrome to the curb. It doesn’t have to be complete; it doesn’t have to be finished, it doesn’t have to be perfect, you just have to do it.