A belief in open science shapes undergraduate Jennings Zhang’s Honors research project

Author: Madelaine Millar

Date: 07.26.21

There are two things that Jennings Zhang, fourth-year computer science and biology combined major at the Khoury College of Computer Sciences, is deeply passionate about: creating software that improves people’s lives and making such software available to as many people as possible. When he’s able to do both – for instance, during his recently completed Honors in the Discipline project to improve fetal neuroimaging – then he’s right where he wants to be.

Jennings Zhang

Jennings Zhang

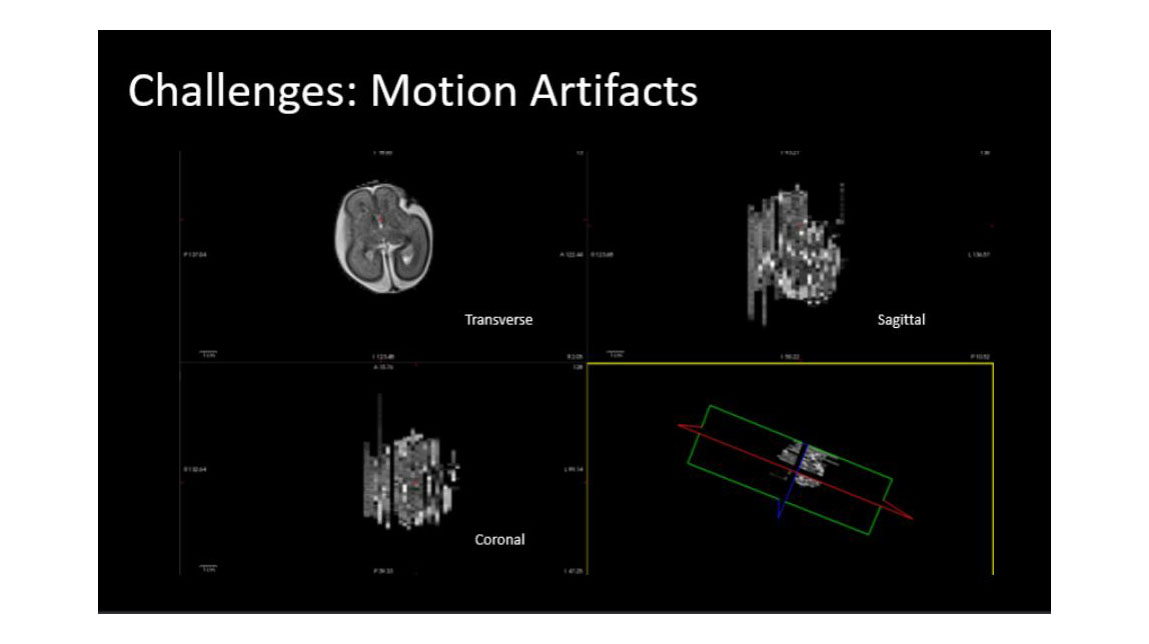

Zhang’s project was two-part. The first part focused on developing a computational pipeline for MRI image reconstruction. Basically, MRI scans of human fetuses in utero tend to have blurry sections called “motion artifacts,” created when tissue or fluids move during the scan. These are a problem because they limit the amount of information doctors can extract. Working with the Fetal-Neonatal Neuroimaging Developmental Science Center at Boston Children’s Hospital, where he had interned back in the spring of 2019, Zhang developed software to correct for those motions, creating clearer and more informative images. He was excited to apply both halves of his combined major in computer science and biology.

Motion artifacts occur when tissue or fluid moves during an MRI scan, creating blurry sections that reduce the amount of information that can be extracted from an image.

Motion artifacts occur when tissue or fluid moves during an MRI scan, creating blurry sections that reduce the amount of information that can be extracted from an image.

“Fetal neuroimaging is inherently interdisciplinary – it combines the most advanced topics in neurology with cutting-edge computer science, where engineers and scientists must work together to achieve their goals,” he said. He was also excited to work on a translational medicine project, where computation is done with real patient data and the impacts are more immediate (as opposed to non-translational science, where the products of research are put into journal publications without immediate impact on the population that was studied).

Though the technical challenges were considerable, they were the least of Zhang’s worries. The larger challenge – and the second half of his project – revolved around enabling non-technical users to interact with cutting-edge medical technologies in a practical, usable way.TThis half of Zhang’s work had to do with the open science initiative the ChRIS project. The project offers a free, accessible way for clinicians and researchers to run powerful medical software more easily, allowing them to make better use of existing research in actual medical practice.

“One of the problems in biomedicine right now is that there’s a wealth of research, but very little of it actually gets used or applied in the clinic, mostly because it’s inaccessible for one reason or another,” explained Zhang. He continued, “Within computational sciences, that accessibility [barrier] is usually the difficulties of how to install and run software.” And that’s where his work came in. Working with the ChRIS project, he developed a way for clinicians to run this software and take advantage of the associated research, without having to go through the learning curve of downloading, installing, and learning to use highly specialized computer programs.

“The platform we’ve developed connects high-performance computing and Linux technologies to the web browser,” he explained. During his Honors in the Discipline project, Zhang deployed ChRIS at the Boston Children’s Hospital and began user testing so that doctors could begin to apply the research that the software opens up.

The fetal MRI image reconstruction software he built is ChRIS-compliant, meaning that it will be seamless for clinicians who want to use it to improve their care. Zhang believes that the relatively new field of fetal neuroimaging represents an incredible opportunity to begin integrating open source and open science ideas into real-world clinical practice and translational medicine efforts. “Because [open source/open science] kind of takes a different approach to science, there’s a lot of new frontier to discover,” said Zhang.

The possibilities continue to stir his imagination. “Part of that is, how can we create these free and open source tools for integrating our novel research into clinical practice? That’s the missing piece—not only in fetal neuroimaging but in most of biomedicine in general,” Zhang explained.

Although his Honors in the Discipline project has ended, Zhang plans to continue to work with fetal neuroimaging and the open science movement. His short-term goal is to expand the deployment of ChRIS locally, so that the clinical staff at the Boston Children’s Hospital aren’t constrained by the learning curve of computational science. He wants them to be able to spend as much time as possible focusing on their research, and as little as possible having to learn how to use a Linux terminal.

In the long term, Zhang hopes that the open science movement will make the kind of computational science he works on more accurate, more reproducible, and more accessible.

“To me, software also is this chance to really rethink how many aspects of our society work,” said Zhang, who summed up his larger goal: “Software is unlike anything in our physical world, because it can be copied for free. And that freedom is precious. Maybe we shouldn’t be creating tools to patent and keep for ourselves, but instead we should be creating tools for the love of creating these tools, for the love of the science of how these tools work, and for the value that these tools bring to lives.”

Subscribe to the Khoury College newsletter

The Khoury Network: Be in the know

Subscribe now to our monthly newsletter for the latest stories and achievements of our students and faculty