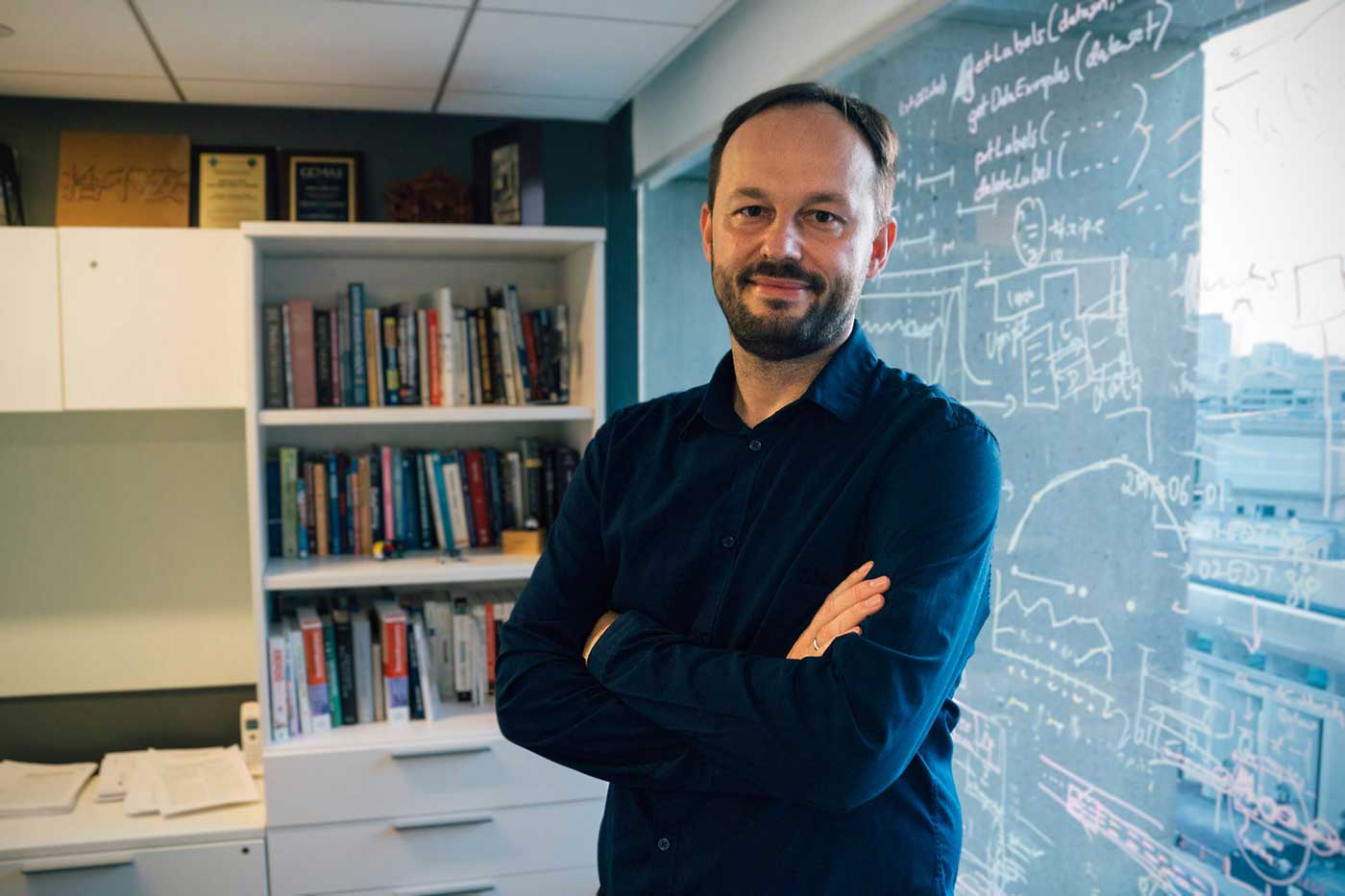

Maciej Kos saw his grandmothers battle dementia. He believes phone data can help find it early

Author: Benjamin Hosking

Date: 04.02.24

In the decades-old search for effective dementia treatments, Maciej Kos sees our everyday smartphones as a powerful tool.

Throughout his doctoral studies in personal health informatics, Kos has made use of digital biomarkers — physiological and behavioral data collected by digital devices such as smartphones and wearables. This data, Kos says, could counter the sobering scope and reality of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

“They are challenges to health systems around the world,” said Kos, who recently completed his doctorate at Khoury College. “According to the World Health Organization, there will be 139 million dementia cases worldwide by 2050.”

Kos’s interest in the subject is more than intellectual. Both of his grandmothers had dementia, and as he grew up close by in his native Poland, he saw the toll it took.

“I was motivated by my experience of losing my grandmothers while they were still alive. For them to not recognize my parents and treat them as strangers — it was very hard,” Kos remembered. “I valued learning from my grandparents through their life stories, but those stories ceased abruptly as their dementia advanced. This reality — that as people live longer, they are more likely to experience dementia — could affect any of us. It’s a tragedy that cognitive impairments cause us to lose so much of our shared human experience.”

Driven by that personal experience, Kos pivoted from his undergraduate studies in economics to information science and health informatics.

“For the regular economics graduate, you won’t be intervening in people’s lives in such a positive way,” Kos said. “I appreciate the elegance of algorithms, but what is most important is that computer science makes an impact on real life.”

From left to right: Kos, Misha Pavel, and Holly Jimison.

From left to right: Kos, Misha Pavel, and Holly Jimison.

Kos’s research is a departure from current methods of cognitive testing, which he notes are not as effective as practitioners would like because they are administered once or twice a year at the doctor’s office. A patient’s performance on these tests is affected by many factors, for example, how well they slept the night before and their stress levels. The tests also aren’t always sensitive enough to pick up small changes in cognition, so clinicians often rely on patients recognizing problems in their daily lives — a classic unreliable narrator problem, and one Kos knows well after his grandmother misreported her medicine intake to her doctor.

Kos’ solution is to gather the personal data our smartphones continuously collect, combine it with modern artificial intelligence and machine learning methods, and use it to continuously estimate changes and trends in cognitive behaviors and functions. In doing so, he found that using more smartphone apps, using them longer, and switching between them more frequently all correlate with slower processing speed and poorer sustained attention. By analyzing the patterns over time, Kos spotted subtle behavioral changes — lower engagement in social interactions, for example — that may be imperceptible for patients, but are informative for clinicians.

“I hope that these methods will help us to diagnose patients, develop new behavioral and pharmacological interventions, and individualize therapies,” Kos said. “It’s exciting that smartphone use data can give insight into cognitive health and help us better understand the progression of neurological conditions. This technology could be used by anyone and it doesn’t require buying any new devices. It makes it especially well-suited for low-income individuals who are frequently ignored and disenfranchised by new expensive health technologies.”

After years of doctoral research funded by the National Institute on Aging, Northeastern’s Network Science Institute and TIER 1 grants, Google, Intel, and the Association of Computer Machinery — and supported by advisers Misha Pavel and Stephen Intille — Kos is looking forward to postdoctoral studies under Art Kramer, an expert in brain health and aging in Northeastern’s College of Science.

“[Studying] computer science at Khoury College gave me a sense of agency, that I can effect change,” Kos said. “That’s Northeastern. It allows you to do this very interdisciplinary, cutting-edge research and collaborate with world-class academics and practitioners.”

Subscribe to Khoury News

The Khoury Network: Be in the know

Subscribe now to our monthly newsletter for the latest stories and achievements of our students and faculty