Northeastern’s Christoph Riedl studies social networks and their influence on innovation

Fri 04.30.21 / Kelly Chan

Northeastern’s Christoph Riedl studies social networks and their influence on innovation

Fri 04.30.21 / Kelly Chan

Fri 04.30.21 / Kelly Chan

Fri 04.30.21 / Kelly Chan

Northeastern’s Christoph Riedl studies social networks and their influence on innovation

Fri 04.30.21 / Kelly Chan

Northeastern’s Christoph Riedl studies social networks and their influence on innovation

Fri 04.30.21 / Kelly Chan

Fri 04.30.21 / Kelly Chan

Fri 04.30.21 / Kelly Chan

With a joint appointment at Khoury College and D’Amore-McKim School of Business, associate professor Christoph Riedl has dedicated his life to exploring the depths of social systems.“My main interest is in social networks: how information and behavior diffuses through networks, how people influence and learn from each other,” he said. “That is really a space that sits at the intersection of different social sciences and benefits methodologically from computational approaches.”

Photo provided by Christoph Riedl

Photo provided by Christoph RiedlHis latest research dives into the dynamics between creative innovation and different rewards systems, as outlined in his recent paper “Incentives, competition, and inequality in markets for creative production,” co-authored with Stefano Balietti from the Mannheim Center for Social Science Research in Heidelberg.

In the paper, they detail the results of a controlled experiment in which real people are tasked with designing images, within certain parameters, using an interactive platform. Then, the images are sent for submission, evaluation, and peer review where they are scored, with certain research participants being awarded tokens as a prize.

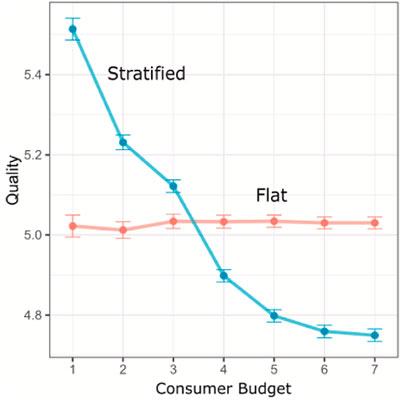

While this process remains the same for all participants, the variability in the experiment lies in the environment in which they submit their images. First, their behavior and work is observed in a “flat” reward structure, where each evaluating institution has the same number and prize amount for the awards. After, participants repeat the process, but instead submit their work in a “stratified” market, which has tiered institutions and thus varying prize amounts depending on the quality of the work.

“When groups of people come together to generate and review products of science, or creative products as we call it in the paper, we look at how they influence each other and what emerges over time,” Riedl said.

What the study found was that there are pros and cons to both structures, with no clear right or wrong. For instance, the stratified market generated more novelty and can help consumers identify higher quality of work, but it does not produce higher quality work overall, had a greater dropout rate due to discouragement they received during evaluation, and distributed rewards more unevenly.

Riedl said he hopes the findings from this experiment will better inform policymakers, who will determine what they value most in creative markets.

“There is no clear answer to how you should implement it,” he said. “Stratified rewards have some positive effects on some people and some negative effects on others. The good thing is we have a better understanding of how this works and how these things interact.”

“I never was the type to use my computer science background to develop algorithms or prove mathematical theorems,” he said. “I’ve always been more interested in applying those methods to answer social science questions.”

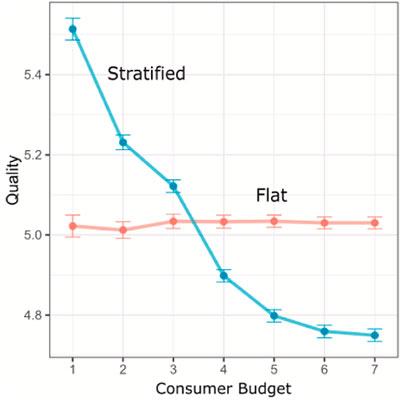

Results from the study show that the average quality of published work is similar in both the stratified and the flat market. However, the stratified market performs a critical filtering function which makes it easier for a budget-constrained consumer to identify high-quality work.

Results from the study show that the average quality of published work is similar in both the stratified and the flat market. However, the stratified market performs a critical filtering function which makes it easier for a budget-constrained consumer to identify high-quality work.Particularly, Riedl enjoys figuring out how to measure notions and ideas that are more abstract and not as easily measured.

“Creativity and innovation often seems like a fuzzy construct,” Riedl said. “But I’m really drawn to research questions where you have constructs that are more difficult to grasp, like ‘What makes a good team?’ or ‘What makes something really creative?’, and find ways to quantify them.”

In addition to teaching, Riedl serves as the director of Northeastern’s Collaborative Social Systems Lab, where he leads a team of graduate students, alumni, faculty, and staff to explore collaboration and social interactions in different settings. He is also a fellow at Harvard Business School’s Institute for Quantitative Social Science as well as the Center for Collective Intelligence at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

For all of his research endeavors, Riedl said his main objective is to advance the quality of scientific innovation by improving the social environments in which scientists work.

“My overarching goal here is better understanding what success means and how we are judging success,” he said. “Specifically with an eye toward success in science, I want to find how we can make science better and how we can produce the best science we can, with the right resources and incentives at our disposal.”

With a joint appointment at Khoury College and D’Amore-McKim School of Business, associate professor Christoph Riedl has dedicated his life to exploring the depths of social systems.“My main interest is in social networks: how information and behavior diffuses through networks, how people influence and learn from each other,” he said. “That is really a space that sits at the intersection of different social sciences and benefits methodologically from computational approaches.”

Photo provided by Christoph Riedl

Photo provided by Christoph RiedlHis latest research dives into the dynamics between creative innovation and different rewards systems, as outlined in his recent paper “Incentives, competition, and inequality in markets for creative production,” co-authored with Stefano Balietti from the Mannheim Center for Social Science Research in Heidelberg.

In the paper, they detail the results of a controlled experiment in which real people are tasked with designing images, within certain parameters, using an interactive platform. Then, the images are sent for submission, evaluation, and peer review where they are scored, with certain research participants being awarded tokens as a prize.

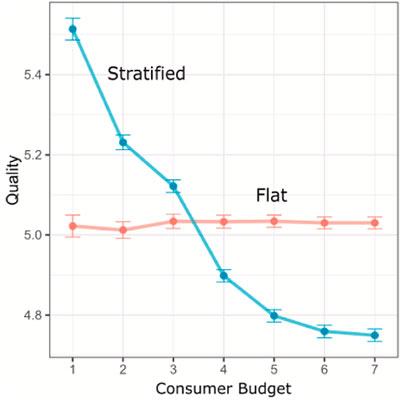

While this process remains the same for all participants, the variability in the experiment lies in the environment in which they submit their images. First, their behavior and work is observed in a “flat” reward structure, where each evaluating institution has the same number and prize amount for the awards. After, participants repeat the process, but instead submit their work in a “stratified” market, which has tiered institutions and thus varying prize amounts depending on the quality of the work.

“When groups of people come together to generate and review products of science, or creative products as we call it in the paper, we look at how they influence each other and what emerges over time,” Riedl said.

What the study found was that there are pros and cons to both structures, with no clear right or wrong. For instance, the stratified market generated more novelty and can help consumers identify higher quality of work, but it does not produce higher quality work overall, had a greater dropout rate due to discouragement they received during evaluation, and distributed rewards more unevenly.

Riedl said he hopes the findings from this experiment will better inform policymakers, who will determine what they value most in creative markets.

“There is no clear answer to how you should implement it,” he said. “Stratified rewards have some positive effects on some people and some negative effects on others. The good thing is we have a better understanding of how this works and how these things interact.”

“I never was the type to use my computer science background to develop algorithms or prove mathematical theorems,” he said. “I’ve always been more interested in applying those methods to answer social science questions.”

Results from the study show that the average quality of published work is similar in both the stratified and the flat market. However, the stratified market performs a critical filtering function which makes it easier for a budget-constrained consumer to identify high-quality work.

Results from the study show that the average quality of published work is similar in both the stratified and the flat market. However, the stratified market performs a critical filtering function which makes it easier for a budget-constrained consumer to identify high-quality work.Particularly, Riedl enjoys figuring out how to measure notions and ideas that are more abstract and not as easily measured.

“Creativity and innovation often seems like a fuzzy construct,” Riedl said. “But I’m really drawn to research questions where you have constructs that are more difficult to grasp, like ‘What makes a good team?’ or ‘What makes something really creative?’, and find ways to quantify them.”

In addition to teaching, Riedl serves as the director of Northeastern’s Collaborative Social Systems Lab, where he leads a team of graduate students, alumni, faculty, and staff to explore collaboration and social interactions in different settings. He is also a fellow at Harvard Business School’s Institute for Quantitative Social Science as well as the Center for Collective Intelligence at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

For all of his research endeavors, Riedl said his main objective is to advance the quality of scientific innovation by improving the social environments in which scientists work.

“My overarching goal here is better understanding what success means and how we are judging success,” he said. “Specifically with an eye toward success in science, I want to find how we can make science better and how we can produce the best science we can, with the right resources and incentives at our disposal.”

With a joint appointment at Khoury College and D’Amore-McKim School of Business, associate professor Christoph Riedl has dedicated his life to exploring the depths of social systems.“My main interest is in social networks: how information and behavior diffuses through networks, how people influence and learn from each other,” he said. “That is really a space that sits at the intersection of different social sciences and benefits methodologically from computational approaches.”

Photo provided by Christoph Riedl

Photo provided by Christoph RiedlHis latest research dives into the dynamics between creative innovation and different rewards systems, as outlined in his recent paper “Incentives, competition, and inequality in markets for creative production,” co-authored with Stefano Balietti from the Mannheim Center for Social Science Research in Heidelberg.

In the paper, they detail the results of a controlled experiment in which real people are tasked with designing images, within certain parameters, using an interactive platform. Then, the images are sent for submission, evaluation, and peer review where they are scored, with certain research participants being awarded tokens as a prize.

While this process remains the same for all participants, the variability in the experiment lies in the environment in which they submit their images. First, their behavior and work is observed in a “flat” reward structure, where each evaluating institution has the same number and prize amount for the awards. After, participants repeat the process, but instead submit their work in a “stratified” market, which has tiered institutions and thus varying prize amounts depending on the quality of the work.

“When groups of people come together to generate and review products of science, or creative products as we call it in the paper, we look at how they influence each other and what emerges over time,” Riedl said.

What the study found was that there are pros and cons to both structures, with no clear right or wrong. For instance, the stratified market generated more novelty and can help consumers identify higher quality of work, but it does not produce higher quality work overall, had a greater dropout rate due to discouragement they received during evaluation, and distributed rewards more unevenly.

Riedl said he hopes the findings from this experiment will better inform policymakers, who will determine what they value most in creative markets.

“There is no clear answer to how you should implement it,” he said. “Stratified rewards have some positive effects on some people and some negative effects on others. The good thing is we have a better understanding of how this works and how these things interact.”

“I never was the type to use my computer science background to develop algorithms or prove mathematical theorems,” he said. “I’ve always been more interested in applying those methods to answer social science questions.”

Results from the study show that the average quality of published work is similar in both the stratified and the flat market. However, the stratified market performs a critical filtering function which makes it easier for a budget-constrained consumer to identify high-quality work.

Results from the study show that the average quality of published work is similar in both the stratified and the flat market. However, the stratified market performs a critical filtering function which makes it easier for a budget-constrained consumer to identify high-quality work.Particularly, Riedl enjoys figuring out how to measure notions and ideas that are more abstract and not as easily measured.

“Creativity and innovation often seems like a fuzzy construct,” Riedl said. “But I’m really drawn to research questions where you have constructs that are more difficult to grasp, like ‘What makes a good team?’ or ‘What makes something really creative?’, and find ways to quantify them.”

In addition to teaching, Riedl serves as the director of Northeastern’s Collaborative Social Systems Lab, where he leads a team of graduate students, alumni, faculty, and staff to explore collaboration and social interactions in different settings. He is also a fellow at Harvard Business School’s Institute for Quantitative Social Science as well as the Center for Collective Intelligence at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

For all of his research endeavors, Riedl said his main objective is to advance the quality of scientific innovation by improving the social environments in which scientists work.

“My overarching goal here is better understanding what success means and how we are judging success,” he said. “Specifically with an eye toward success in science, I want to find how we can make science better and how we can produce the best science we can, with the right resources and incentives at our disposal.”

With a joint appointment at Khoury College and D’Amore-McKim School of Business, associate professor Christoph Riedl has dedicated his life to exploring the depths of social systems.“My main interest is in social networks: how information and behavior diffuses through networks, how people influence and learn from each other,” he said. “That is really a space that sits at the intersection of different social sciences and benefits methodologically from computational approaches.”

Photo provided by Christoph Riedl

Photo provided by Christoph RiedlHis latest research dives into the dynamics between creative innovation and different rewards systems, as outlined in his recent paper “Incentives, competition, and inequality in markets for creative production,” co-authored with Stefano Balietti from the Mannheim Center for Social Science Research in Heidelberg.

In the paper, they detail the results of a controlled experiment in which real people are tasked with designing images, within certain parameters, using an interactive platform. Then, the images are sent for submission, evaluation, and peer review where they are scored, with certain research participants being awarded tokens as a prize.

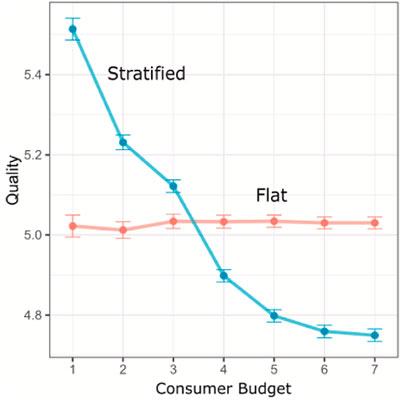

While this process remains the same for all participants, the variability in the experiment lies in the environment in which they submit their images. First, their behavior and work is observed in a “flat” reward structure, where each evaluating institution has the same number and prize amount for the awards. After, participants repeat the process, but instead submit their work in a “stratified” market, which has tiered institutions and thus varying prize amounts depending on the quality of the work.

“When groups of people come together to generate and review products of science, or creative products as we call it in the paper, we look at how they influence each other and what emerges over time,” Riedl said.

What the study found was that there are pros and cons to both structures, with no clear right or wrong. For instance, the stratified market generated more novelty and can help consumers identify higher quality of work, but it does not produce higher quality work overall, had a greater dropout rate due to discouragement they received during evaluation, and distributed rewards more unevenly.

Riedl said he hopes the findings from this experiment will better inform policymakers, who will determine what they value most in creative markets.

“There is no clear answer to how you should implement it,” he said. “Stratified rewards have some positive effects on some people and some negative effects on others. The good thing is we have a better understanding of how this works and how these things interact.”

“I never was the type to use my computer science background to develop algorithms or prove mathematical theorems,” he said. “I’ve always been more interested in applying those methods to answer social science questions.”

Results from the study show that the average quality of published work is similar in both the stratified and the flat market. However, the stratified market performs a critical filtering function which makes it easier for a budget-constrained consumer to identify high-quality work.

Results from the study show that the average quality of published work is similar in both the stratified and the flat market. However, the stratified market performs a critical filtering function which makes it easier for a budget-constrained consumer to identify high-quality work.Particularly, Riedl enjoys figuring out how to measure notions and ideas that are more abstract and not as easily measured.

“Creativity and innovation often seems like a fuzzy construct,” Riedl said. “But I’m really drawn to research questions where you have constructs that are more difficult to grasp, like ‘What makes a good team?’ or ‘What makes something really creative?’, and find ways to quantify them.”

In addition to teaching, Riedl serves as the director of Northeastern’s Collaborative Social Systems Lab, where he leads a team of graduate students, alumni, faculty, and staff to explore collaboration and social interactions in different settings. He is also a fellow at Harvard Business School’s Institute for Quantitative Social Science as well as the Center for Collective Intelligence at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

For all of his research endeavors, Riedl said his main objective is to advance the quality of scientific innovation by improving the social environments in which scientists work.

“My overarching goal here is better understanding what success means and how we are judging success,” he said. “Specifically with an eye toward success in science, I want to find how we can make science better and how we can produce the best science we can, with the right resources and incentives at our disposal.”